Writes

Writes is a collection of new work by writers from Melbourne’s

West and beyond, published online. Curated by Bigoa Chuol.

About the Authors

The Disabled QBIPOC Collective

The Disabled QBIPOC Collective is a group of four writers, who identify as disabled and queer Black people, Indigenous people, and People of colour.

CB Mako

CB Mako is a non-fiction, fiction, and fan-fiction writer. Winner of the Grace Marion Wilson Emerging Writers Competition, shortlisted for the Overland Fair Australia Prize, and longlisted for the inaugural Liminal Fiction Prize, cubbie has been published in The Suburban Review, The Lifted Brow, Mascara Literary Review, The Victorian Writer, Peril Magazine, Djed Press, Overland, Liminal Fiction Prize Anthology (via Brow Books, arriving in 202X), and Growing Up Disabled in Australia (via Black Inc Books, arriving in 2021).

Pauline Vetuna

Pauline Vetuna (Gunantuna – indigenous to Papua New Guinea) is a writer, artist, curator raised and living on Kulin Nation lands. For many years, Pauline has been involved in grassroots, community-based and led arts projects in the western suburbs of ‘Melbourne’; through which she has explored art creation through a variety of mediums. Currently, her community engaged creative practice is focused on creating spaces for disabled BIPOC & disabled queer and trans people to pursue justice, tell their stories, create art – and find healing in solidarity and community.

Hannah

Hannah, (Nirae Baluk, of the Hamilton/Walsh line) is a professionally awkward, Deaf/Disabled storyteller.

Gemma Mahadeo

Gemma Mahadeo is a writer and occasional performer who came to Australia in 1987, after living in England and the Philippines. Their work has appeared in numerous Australian print and online journals, and recent festival appearances and conferences include 2019’s Freeplay Independent Games Festival, and the Emerging Writers Festival, and speaking at the launch of the Diversity Arts Australia ‘Shifting the Balance’ report. They are currently poetry editor of Concrete Queers zine, and reviews editor for the Melbourne Spoken Word website. They identify as queer, disabled, and very much in love with cats, tea, beer, books, and music.

Image provided by the Disabled QBIPOC Collective.

Writes is supported by Malcolm Roberson Foundation.

Who We Are

Pauline Vetuna

Our lived experiences of disability, race, culture, queerness and class are all very different, as are our voices, storytelling styles and our writing.

We want to give readers an insight of what it means to live at these incredibly complex politicised intersections, especially during the pandemic.

In the solace of mutual aid, manoeuvring and unravelling in this climate of disruption and uncertainty, we share the possibilities we can imagine. Furthermore the possibilities we do not have the luxury of imagining and why. Community mutual aid is, has been and will continue to be essential for disabled, queer, BIPOC going into the future.

*

When the four of us first formed our collective in 2019, it was out of the sheer necessity of mutual aid and support; the common ground we share of being queer BIPOC writers, being disabled and living with mental health disabilities. Trying to function and thrive in a world that is often hostile to us means collective advocacy and so-called “activism” are simply a necessity.

We came together as a collective for our children, families, our friends, community and ourselves.

We have all experienced stigma. We have all experienced financial hardship.

We have all sustained traumas.

We have all battled physical and non-physical access barriers and continue to regularly.

And we have all learned a BUNCH in the process of doing all these things and have much to share, as other disabled people do too.

We are now working at a compassionately and sustainably slow pace to build a collective and space, which eventually other disabled queer BIPOC writers and artists, can find community, accessible resources and the support we need as disabled people to flourish as creatives and shape the world around us to be welcoming of us, and by extension, all people.

That includes learning to be allies to one another and our different disabilities too. We do not by any means represent all experiences of disability, and part of building together is the four of us doing work to listen and continuously learn about different disabilities too. Learning how to be allies to others.

The three of us who are settlers have a responsibility to our First Nations’ colleague and friend to prioritise the doing of allyship with First Nations people.

The two of us who are not Black have a responsibility to check anti-Blackness.

The three of us who aren’t parents have a responsibility to be allies to our colleague and friend who is. And so on, and so forth.

THE FUTURE IS ACCESSIBLE, and this is how it will be built.

Pandemic: Side Effects May Include Dissonance

Gemma Mahadeo

My body does the things it needs to survive, and my mind is in a balloon filled with helium, on a thin string tied tightly to my wrist. I can’t reach the balloon, the attached string is very worn, threadbare.

The night terrors have begun again. I’m worried about waking up my housemate who is prone to tantrums about any sound I make. Who cares what causes the terrors. I glance around my room. At least the flashbacks to an unsafe living space have ceased. How long for? I wonder, inching myself out of bed.

The day starts like it did pre COVID-19: feed Puss – the only being who loves me unconditionally. She always gets breakfast before me – I only eat because of the meds. Not much has changed since enforced social isolation, except now one of my housemates lives downstairs and made it an unwelcome space. Only to me. Puss no longer sleeps in her favourite armchair.

Around lunchtime, I ache to play a musical instrument. It releases anxious energy. The balloon above my head is reachable during practice. To keep the peace, I don’t practise any instruments. Uncontrollable shaking will take place instead. My cat will always be near when this happens. Yes, relaxed measured breathing; yes, diazepam, then another dose thirty minutes once the shaking is so violent. You know those medical TV programmes where the paramedics are struggling to strap someone to a gurney? Or when the body goes into extreme shock? You watch your outstretched limbs bouncing up and down but this does not feel like your body. Wait 20-30 minutes. Get into foetal position on bed, and stay like this for a while. Next stage: nausea spasms, which escalate to dry retching. Running to the bathroom to only throw up streams of saliva is deeply humiliating because it is so noisy. God, please no one see or hear me. If food or drink has been consumed within the hour, then at least expelling that would provide relief, as well as less noise. You know what you need to do: wash hands thoroughly, then stick fingers down throat. This helps the spasms subside.

Once the retching settles, clonazepam. The entire day is a write-off. Clonazepam affects my coordination so much that I won’t be able to drive, go downstairs without clinging onto the rail like it is my life source, or prepare meals. I want a human to hold me, then bring me cups of tea in bed. Have a human care for me: what an indulgent thought! I berate myself.

The balloon’s too high. My body wants so much to cry but the high dosages of my antidepressants means i won’t. My room is small, I am fed up of being confined to it, but tell myself off for being so ungrateful: you are not in hospital. You ignore the loneliness that comes with sharing a house with people who don’t want to learn to care. You’ve been through worse. A white queer, and a woman of colour, as housemates, and neither of them were actually allies. Isn’t that hilarious? I joke inwardly. Do I have chosen family or do those people just pretend? Don’t text, don’t instant message anyone. You pester them enough. Get back in touch when you’re feeling better. You’re less of a burden then.

The balloon is out of sight. Reminder: now that the Jobseeker payments have been temporarily increased, go and get new glasses. You’ve needed them for years, but one fortnight was always for rent, and the other for survival. It’s a relief that your night medication will help you sleep. Save money! Take them at dinner and skip a meal. This isn’t foolproof, sadly. You might wake a few hours later, with the type of hunger even you cannot ignore. My appetite is reliably absent, till the body approaches starvation levels. Go downstairs – carefully – and make a huge mug of beetroot or matcha latte. The milk is almost like a meal…?

Momentarily, your body and mind are almost reconnected. The balloon taunts me by floating next to my head, occasionally grazing my ear, its string snaking up along my arm. Remember to wash your hands, but sanitise them again anyway when back upstairs, to enjoy the sting where you’ve picked skin till you’ve bled. The balloon starts drifting back up. More diazepam and fall asleep sometimes cradling your cat. You forget all about where the balloon might be. The quetiapine helps so much, but it takes hours to fully wake up the morning after. Thank goodness it hasn’t increased my appetite. It means I don’t have to buy as much to eat. More money saved.

Maybe – a big maybe – tomorrow will be the right one, where you’ll have the guts to shower and pick up scripts and groceries. You remind yourself your cat won’t love you any less if you can’t do it.

Which day is the one where I wake up, and the balloon is next to me?

A Slow Life in a Pandemic

CB Mako

How do you write in a pandemic? In a lockdown, quarantine, your fast, active life grinds to a halt.

I’ve been known to be slow most of my life. Growing up, my parents would often tell me to hurry up. When I couldn’t catch up, I was usually left behind. There seems to be a certain speed that ableism wants: to be exact, on time, quick, clockwork, at a steady fast pace. There’s fast fashion, fast cycling, fast cars. Everyone wanting to be the first to cross the finish line. Those who cannot catch up are left behind.

We, the disabled, see life zoom past us at unrelenting speed, pushing us to the side-lines. In society’s capitalist, consumerist life, we are those whom you have left behind. Those who you didn’t have any second thoughts about during the bushfires, or in national emergencies. Those whom you didn’t plan to include, whose existence didn’t even cross your mind.

But we are here.

Now that a worldwide pandemic has forced you to slow down to our speed, you notice us. We are your neighbours who need extra help acquiring food and groceries, who do not have the capacity or financial means to hoard or panic-buy.

But we love slow. Slow: the pace which my offspring and I have deliberately chosen. We move at our own pace. We stop and smell the flowers while in our cargo bike. We see the butterflies greet us as we pedal at a leisurely pace. I often tell my kids that life is a journey. A slow journey.

*

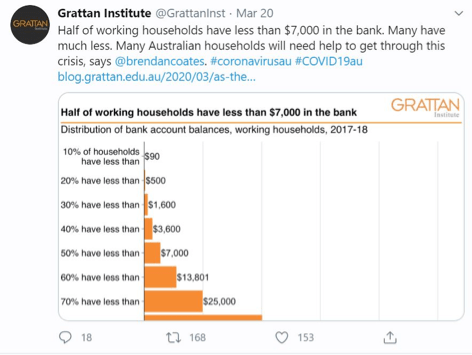

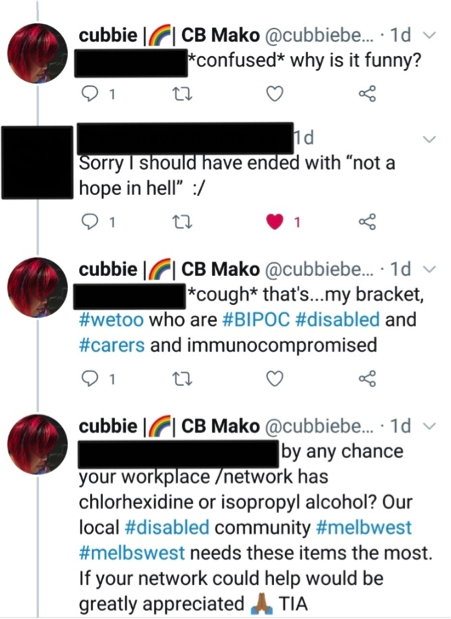

When the pandemic lockdown started, I stared at my Twitter feed, confused. An able-bodied, fully employed, cis-het, child-free, white woman laughed at a tweet I retweeted from Grattan Institute.

At first, I was perplexed by her tweet. I then asked,

Did she mean that there was no hope in hell for people with less than $500 would survive the pandemic? I had less than $500 in my bank account.

If the abled woman had more resources, would she share? If I cajoled her, would she reply and help? Was she among the hoarders of toilet paper? Or those who were fast enough, with money and space to panic-buy and empty supermarket shelves? No offer of help came from the laughing white woman, with all her money and her resources despite her financial and physical capacity to reach out and help.

*

On 17 March 2020, I was late to my very first online video meeting on a platform called Zoom. The Zoom meeting was called ‘Narrm Community Care for Coronavirus’ . Among highly energised young, able-bodied group of people, they spoke of Google documents and mapping out and—

I popped up into the Zoom feed and introduced myself. I went straight to the point. We needed their help. Now. ‘We can’t find liquid hand sanitisers for our immunocompromised child.’

Silence greeted me.

And then they continued down their path of conversation.

On Twitter, many established and privileged white and white-passing writers and authors revelled in the isolation – having time to write, showing off palatial writing rooms, with large, opulent desks. They had time to read and took snapshots of newly purchased books. They had the means, after all, to heed the call of the hashtag #BackYourBookshop on social media.

My family, on the other hand, needed food on that very same week. How could they not worry about food on the table?

The first to respond to our – before Melbourne food delivery services got organised – were from fellow queer Culturally And Linguistically Diverse (CALD) and Black, Indigenous, People of Colour (BIPOC ) artists.

In the pouring autumn rain, a fellow queer artist dropped off much-needed alcohol-based liquid sanitiser. Another group of QBIPOC artists anonymously dropped off a box of veggies, fruit, and meals at our doorstep. I hadn’t eaten that night, too worried where to find food to feed my family of four. I cried, as I ate my first spoonful of a delicious, freshly cooked meal.

The next day, an Express Post parcel arrived from an immunocompromised family: a big bottle of hand sanitiser. Another day, a large box, full of books, arrived. Brand new books from a CALD friend across the city. There were books for my kids, for myself, so many books that I in turn was able to share with fellow writers who had no capacity to buy books in a pandemic. I knew many who had low funds due to covering medication costs. The most empathic people were like us, struggling, helping each other in an informal network. The Collective made me hopeful that we could indeed survive this pandemic.

/post/

Hannah Morphy-Walsh

I thought I would be less tired by now.

I stopped going to work over two months ago, when the cat was already out of the bag. Before the panic buying. First it was the toilet paper, then essential medicines. For two months, we had a bottle of isopropyl alcohol to keep us going through the crisis.

My sister left the city, and my father insisted on staying. The flow of information has increased. The flow of bad information has increased. Medicine shortages are nerve-wracking when you’re more than two phone calls away from a functioning body. I found out about the shortages the same way most people did: I went to the local pharmacy. Has there has been relief from the widespread medicine shortages? I would know by not having to enter a process of advocacy, just to fill a script. Perhaps, then, the uncertainty would lift.

I bought hedges and soap.

People deal with fear in different ways. Some withdraw, trying to become impossible to reach. Others lash out at the people around them.

I know that time is still passing because the hedge brushes the fence and because other people still think in terms of days. We are counting the days we are still alive. Some, of course, have stopped counting. And the rest of us go on. I have been alive for 9,638 days. It is the same world, only people have changed.

Work goes on. We are looking for ways to stay busy. I open my computer. I close my computer. Somewhere in the middle, I lose time. To break up the week, we buy food. Every step of this process is carefully negotiated beforehand, and still turns into a fight. I don’t know how to stop fighting. My father suggests meditation and more sleep. I tell him this is rich coming from the man who has chosen to live alone, and we do not talk for several days.

The next time we talk, I am reminded of the lectures he used to give me as a child. I am asking him to limit his time in heavily patrolled areas, to stay out of stores unless it is a planned purchase, and to avoid doctors’ offices and outpatient waiting rooms. He notes the comparison, but not the worry underlying it. There is a very real possibility that he will die before his time, and I am afraid of tempting fate. We do not argue, though our conversations are tense. Mostly, we talk about work, as if everything is normal. In many ways, it feels more normal than normal did before.

I see my neighbours more than I used to, but we talk less. I think they hear us, at night. It is easier to see the patterns now. Most of my friends have adjusted to a largely distanced world, and some are beginning to thrive. We do not feel video-conference fatigue. People are somehow easier to cope with now, that they have become signals on a screen. These signals look forward to resuming life as they did before.

I’m not sure I feel the same.